Welcome to The Bakers' Cottage, a newsletter where I share stories, recipes, and the kind of kitchen projects that make me linger by the oven, waiting for something to rise, brown, or crack just so. If you're new here, thank you for reading. If you're a free subscriber, consider upgrading to support this space.

Today’s post is about a cake that looks burnt.

Tourteau fromagé comes from the Poitou-Charentes region of France, a place known for its butter and cheeses, its windswept coast, its quiet. It’s a goat cheese soufflé cake, baked in a thin, flaky crust and scorched to an improbable blackness.

A cake that wears its mistake as a badge of honour.

The burn is deliberate. In the oven, the top darkens to a charcoal crust, cracking here and there as it domes. Beneath it, the crumb is impossibly light, airy, with a slight tang, thanks to the chèvre frais. It’s sweet, not savoury – best eaten in slivers, with a cup of coffee or a spoonful of fruit compote on the side.

In today’s post, I’ll take you through the process, from the rough pâte feuilletée (and not brisée like the original – just don’t tell my grand-mère) base to the cloud-like filling.

I hope you’ll enjoy it. And if you bake it, let me know – there’s nothing better than hearing how a recipe travels.

Read on for the full recipes and notes.

This is a rather long post, so if your email cuts out, you can view it in full on the website or in the app.

There, in my grand-mère’s cagibi – an unassuming door off the red-and-white tiled kitchen – among rows of wine bottles, tins of haricots verts, and bags of flour stacked high, tucked between a Tupperware of cassonade with a dried vanilla pod and galettes nantaises neatly sealed in rustling parchment, sat a tourteau fromagé. It was always there. Wrapped in a plastic bag with yellow letters and a red wire tie. Its blackened dome, smooth and brittle, enclosed a pale yellow crumb so light it felt as though it might disappear between my fingers.

Every morning in Fouras, the camionnette would rattle down the street, klaxoning as it passed. The boulanger delivered bread straight from the truck, or if you weren’t home, you’d leave a cloth bag by the fence with a note tucked inside – trois baguettes bien cuites, un pain de campagne, and sometimes: un tourteau fromagé.

A small fishing village turned summer paradise, Fouras sits on the west coast of France, just south of La Rochelle. It is surrounded by salt marshes, slow-moving rivers and channels, woods and fields. Long, tidal beaches, where the ocean leaves behind great jellyfish and tangled seaweed on the sand. A fort, built by Vauban, watches over the coast, its stone walls weathered by centuries. Along the walk by the ramparts, wooden carrelets – fishing huts on stilts – stand over the water, their square nets suspended in the air.

In the mornings, we'd watch the tide roll in and out, trace patterns in the sand, and watch the puces des sables jump around them. We'd swim in the retenue d’eau of la Grande Plage, while grand-mère waited in the shade under the pines lining the stone walls. In the afternoons, we'd walk to mémé – my great-grandmother – for a goûter of gaufres. But sometimes, after his sieste, grand-père would join us at the beach, a tourteau fromagé in the basket of his bicycle. We'd open the wire tie and use the plastic wrapper as a makeshift tablecloth.

I ate it the same way each time. The pâte brisée, golden and firm, was left behind. It was the inside I wanted – the contrast between its cloud-like centre and that fragile, crackling crust, burnt to the edge of bitterness.

L’histoire

The story of tourteau fromagé begins in Deux-Sèvres, a département of Poitou-Charentes (an old administrative region – it was merged with Aquitaine and Limousin to form the new region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine in 2016), where rolling pastures and limestone hills make for rich grazing land. This is chèvre country, home to some of France’s most renowned goat cheeses – Chabichou, Mothais sur feuille. It’s no surprise, then, that fresh goat cheese found its way into cakes.

In a 1983 publication, Jacqueline Gay and Hughette Nicolas recount childhood memories of tourtès, written in both French and patois poitevin, tracing the possible origins of the cake known as fromageau:

"But will we ever know the name of the modest cordon bleu, in a coarse hemp apron, who was the first to add a little sugar, flour, and a few eggs to her delicious fresh goat cheese? This became the 'fromageau' of Sainte-Néomaye – the cheese tart."

Before the burnt dome that I’ve come to love, there was something simpler. In the past, it was common to bake simple goat cheese tarts in farmhouse ovens, their rustic pâte brisée crisping in the residual heat of the embers. A cheesecake of sorts – though the French would never call it that – made with nothing more than fresh goat cheese, sugar, and eggs. It went by many names – fromageau, fromageou, tourtê feurmajhé, tourtéâ.

And then, at some point, someone let it burn.

Some say it was a mistake – a cake left too long in the oven, swelling as it baked, its surface darkening far beyond golden. When it was finally pulled out, the damage seemed done – the top was scorched. But when the baker cut into it, she discovered something unexpected. Beneath the black, brittle crust, the cake was impossibly light, airy, with a soft tang from the cheese.

Others claim it was a way to test the heat of the oven: if the top burned too quickly, the fire was too strong; if it barely browned, the embers needed stoking.

We might never know the truth, but the burnt top is now very much deliberate – something I’ve had to tell Sienna many times, as she simply refused to believe me while I pulled two tourteaux out of the oven.

From market stalls to attics

For a cake so deeply tied to its terroir, tourteau fromagé has remained largely absent from the narrative of French gastronomy. It is not a pâtisserie de luxe, not a towering showpiece displayed behind glass. It belongs instead to the quiet corners of rural life.

Yet, if you look closely, traces of its presence appear in the literature and folklore of Poitou-Charentes.

In L’Art Culinaire, a historical culinary journal, tourteau fromagé is listed as part of a traditional menu poitevin, alongside roasted chevreau and a simple potage au farcis. This speaks to its place in regional meals – not a grand dessert, but an expected and familiar ending to a meal, much like a wedge of cheese. Another entry in L’Industrie du Beurre describes how tourteau fromagé was long associated with celebrations, particularly in farmsteads where milk and cheese were plentiful.

In La Vie de famille (1993), a collaboration between the photographer Robert Doisneau and writer Daniel Pennac, a witness recalls a wedding in Poitou in the 1950s:

"I remember above all the tourteaux. An incredible number of cakes, covering the entire attic floor of Aunt Reine’s house. Their black crusts gleaming beneath the white dresses of the bridesmaids, who were shaking out their gowns in the attic."

(La Vie de famille, 1993, p. 9)

The image is as evocative as it is matter-of-fact. Not a plated dessert, but a presence – a cake that simply is, as much a part of the day as the dresses themselves.

And it wasn’t just weddings. Tourteau fromagé appeared wherever people gathered – whether in the hush of an attic on a summer morning, where dust glistened in the low sunlight filtering through a small window, or in the bustle of an open-air market, lined up in rows on wooden trestles.

If you’ve ever been to a marché de rue in France, you’ll know the rhythm of the morning – the trickle of shoppers before the rush, the scent of warm bread mingling with ripe peaches, the metallic clang of a scale weighing wedges of cheese. Stalls that spill over with thick braids of garlic and bunches of fresh herbs, while the maraîchers call out their prices en cacophonie.

And then, there are the cakes. Not the delicate ones of a pâtisserie window, but the sturdy, familiar kind: tartes aux pommes with their golden spirals, dense quatre-quarts, and, in Poitou-Charentes, tourteaux fromagés.

This is how Aguiaine, a 1970s ethnographic review of central-western France, describes them:

"The trestle tables covered in white cloths, lined with plump fromagés whose dark brown domes and golden crust enclosed the beautiful yellow crumb."

(Aguiaine, 4, 1970, p. 326)

I can see them – their burnt tops standing in sharp contrast against the white linens, lined up at the marché, as much a staple as baguette and butter.

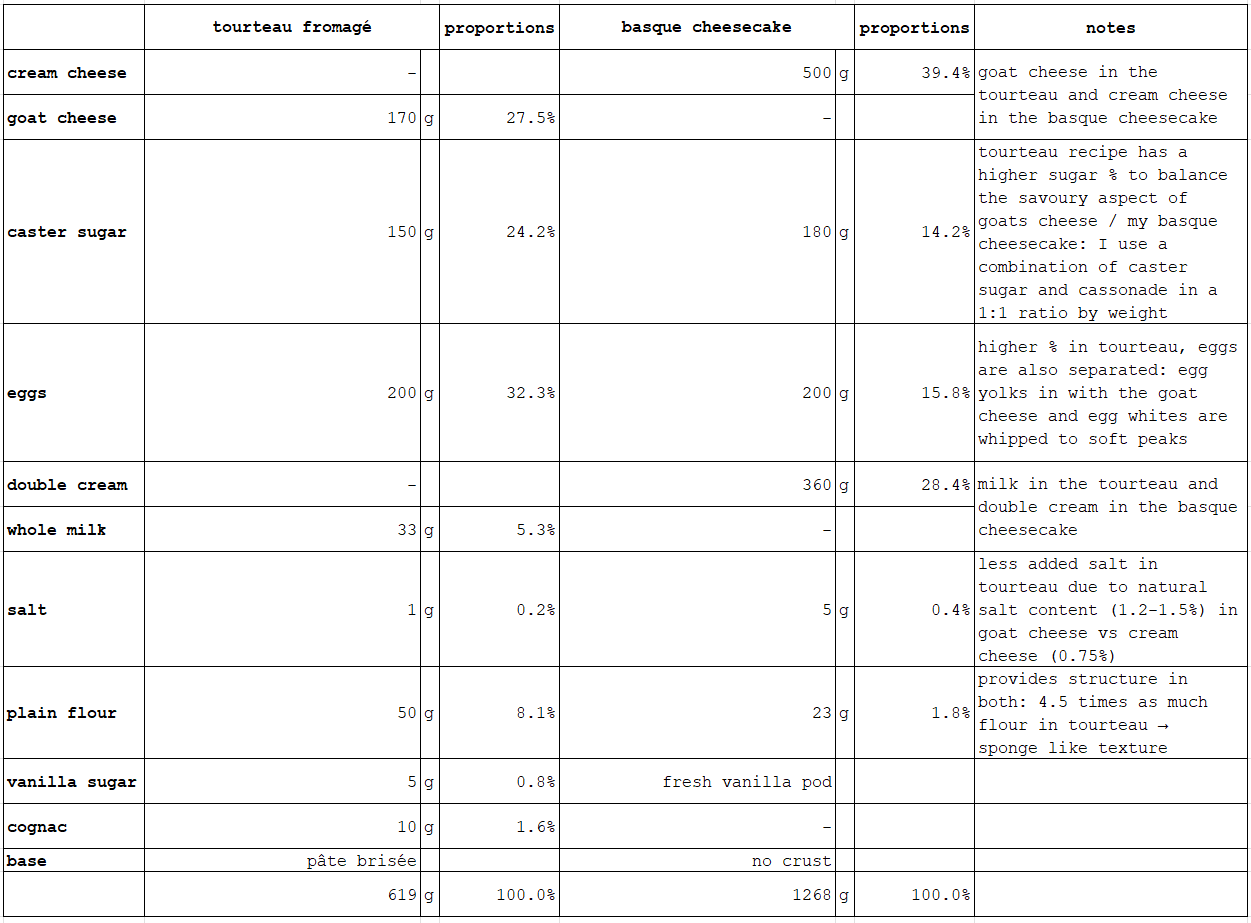

The other burnt cheesecake

A few hours’ drive down the coast, where the Atlantic meets the Pyrenees, another cheesecake proudly wears its burnt top. Basque cheesecake, born in the kitchens of La Viña in San Sebastián, has since travelled far beyond its origins, appearing on menus from Tokyo to New York – unlike tourteau fromagé, which remains quietly rooted in the Poitou-Charentes countryside.

The differences go beyond fame. Basque cheesecake is crustless, its batter rich with cream cheese and double cream, baked at a medium-high temperature until its top blisters and caramelises. It is dense and creamy. Tourteau fromagé sits within a sturdy pastry shell, its airy, soufflé-like interior carrying the tang of fresh goat cheese. It is baked first at a high temperature, often with the grill on, then left to bake longer at medium-high heat until it domes.

Tourteau fromagé du Poitou-Charentes

The only thing left to do now is bake. It starts with a rough pâte feuilletée – admittedly not traditional.

Yes, I couldn’t help but wonder if puff pastry would be even better than the pâte brisée I always left behind – the crisp, flaky layers against the sponge-like crumb. It’s my go-to for quiches and flans pâtissiers.

I suspected it might work, and when I tried it, it did. You could use good-quality store-bought, but rough puff is a low-effort alternative. And I’m always surprised that the raw rough pâte feuilletée tastes more like my grand-mère’s pâte brisée than any pâte brisée that’s ever met my kitchen bench.

The recipe makes more pastry than you’ll need, but I never say no to extra puff pastry in my fridge – or in my freezer, where it keeps beautifully for up to three months. And since it takes no more time or work to make a full batch than a half batch, why not? As Nigella once wrote: if you’re going to get wet, you might as well go swimming!

If you’d like to go fully authentic, here’s my recipe for pâte brisée:

Pâte brisée

In a large bowl, mix 250 g plain flour with ½ tsp fine sea salt. Cut 125 g cold salted butter into small cubes and rub into the flour until the mixture looks sandy, with some larger bits remaining.

Make a well in the center, add 1 egg yolk, and mix in about half of 50 g ice-cold water. Stir until the dough just comes together, adding more water if needed. Turn onto a lightly floured surface, press into a disc (no kneading), wrap, and chill for at least an hour.

When ready, roll out on a floured surface, turning as you go. Use for tarts, pies, or anywhere good pastry is needed.

Or you could skip the pastry entirely. I did, and it was everything I wanted.

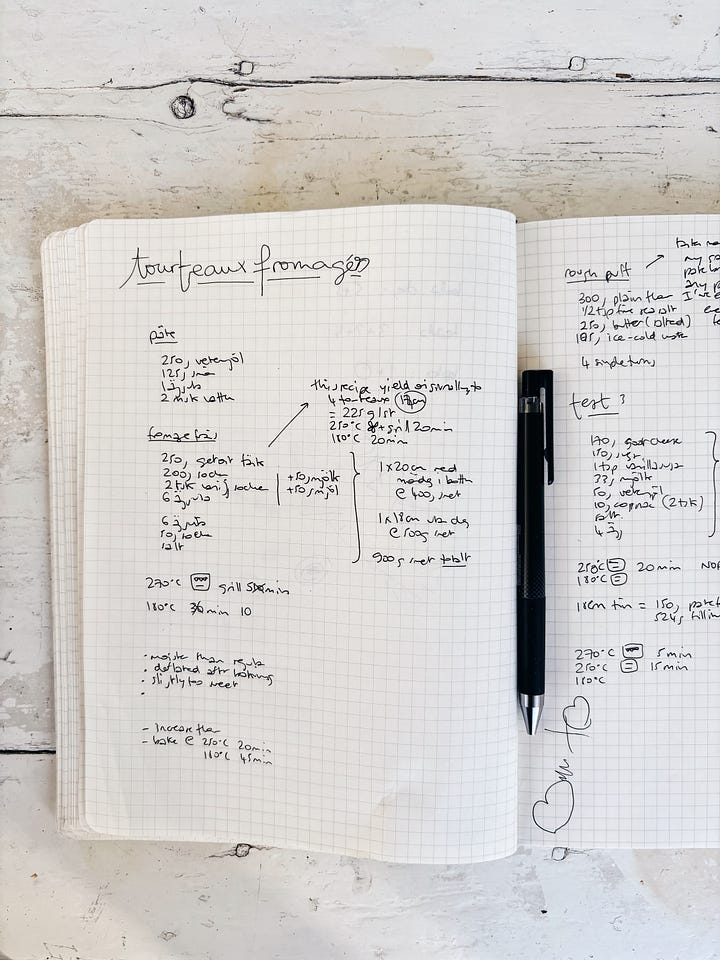

Recipe tests & notes

Test 1: Pâte brisée

Tried pâte brisée. Buttery and crumbly, but I found myself peeling it away.

Note: A classic choice, but I never truly loved it.

Test 2: Skipping the pastry

Baked without a crust.

Notes: Closer to a fromage blanc cheesecake or Japanese cheesecake. Amazing with lightly whipped cream and fresh berries.

I might never make it with pastry again.

Baking method & tasting notes for tests 1 & 2

Baking

Started at high heat 270°C, with the grill mode on, and baked until the top developed a deep, charred black crust – 5 minutes. There was smoke.

Lowered the temperature to 180°C, then baked until puffed – 35 minutes.

Texture

Soft and mousse-like (you know the sound of a spoon sinking into a thick mousse?).

Much moister than the tourteaux of my childhood.

Delicious in its own way, but not quite what I was trying to recreate.

The dome deflated as the tourteau cooled down, and we ended up with a flat tourteau.

Taste

Slightly too sweet – I’ll reduce the sugar in the next batch.

I haven’t quite figured out how to keep the dome from deflating as it cools.

Should I try cooling it upside-down, à la panettone or angel food cake?

Should I bake longer or increase the amount of flour in the filling?

Is it because I’m not using a spherical mould?

Oh, that’s something I should mention. Tourteau is traditionally baked in a metal moule à tourteau fromagé – a bowl-shaped tin, about 14 cm wide and 7 cm high. But with my tin cupboard already on the verge of overflowing, I used an 18 cm aluminum cake tin instead.

Tip: Avoid ceramic or glass – they might not withstand the initial heat from the grill.

To-do

Increase flour in the recipe and reduce sugar.

Add cognac.

Test a new baking method:

270°C grill mode for 5 minutes

250°C for 15 minutes

180°C for 45–60 minutes – will this help the dome hold its shape?

Test 3: New ratios & puff pastry

I did a few things differently this time round. In the batter: less sugar, more flour, and a dash of cognac. On the outside: puff pastry.

Baking

270°C, grill mode on, 5 minutes

250°C 15 minutes

180°C 40 minutes

Texture

The top held more of a dome shape as it cooled.

Once completely cool, the centre dipped slightly, while the edges remained puffed up.

To maintain a fully domed shape, it likely needs a longer bake.

When sliced:

Edges – light and airy.

Centre – moister, denser, but still mousse-like.

Taste

Loved the addition of cognac.

Sweetness was well-balanced.

Could reduce the sugar slightly more if needed.

I felt like the puff pastry really elevated the tourteau. However, I do wonder how long it will stay crisp before softening from the moisture in the filling.

To-do

Increase baking time to 60 minutes, then assess and adjust as needed.

Notes

On salted butter

If you’d asked me years ago about my thoughts on salted butter, I might have given a plain: Non!

But after living in Sweden for the past ten years, I now bake exclusively with salted butter – and honestly, I’m never going back. That said, I have to admit it makes writing recipes a bit trickier, as the salt content in butter varies widely across the globe. Here in Sweden, it’s typically 1.2%.

Tip: If using unsalted butter, just add a little extra salt and adjust to taste.

On vanilla sugar

Vanilla sugar is a staple in many French and Swedish homes, but a teaspoon of vanilla extract or vanilla bean paste will work just as well.

If you’d like to make your own vanilla sugar, it’s simple. I always collect used vanilla pods, wash them if needed, and leave them to dry in an open glass jar in my skafferi [pantry] until crisp. Then, I grind 3 dried pods with 300 g caster sugar into a fine powder and store it in an airtight container.

On cognac

Cognac is entirely optional, but I couldn’t leave it out. Dark rum would also make a lovely addition – however untraditional it may be.

On incorporating whipped egg whites

When folding whipped egg whites into a denser batter – or any time I am incorporating a light mousse-like texture into something heavier – I always start by whisking in about one-fifth of the whipped egg whites vigorously. This lightens the base, making it easier to fold in the rest without deflating the air you’ve worked into them.

For the remaining egg whites, switch to a silicone spatula and fold gently. Start from the centre of the bowl, lift the batter up the sides, rotate, and repeat. Do not stir from one side of the bowl to the other – always work from the centre and up the sides to keep as much air in as possible.

MAKES one 18cm tourteau

For the rough puff pastry

300 g all-purpose flour

1/4 tsp (2 g) fine sea salt

220 g cold salted butter, cut 2mm slices

100 g ice-cold water, plus more as needed

For the filling

170 g fresh goat cheese

130 g + 20 g caster sugar

4 eggs, separated

30 g whole milk

40 g plain flour

a pinch (1 g) of fine sea salt

1 tsp (5 g) vanilla sugar

7 g cognac (optional)

Make the rough puff pastry

In a medium bowl, mix the flour and salt. Slice the butter thinly – a Swedish cheese slicer is perfect for the job – and toss it in the flour to coat.

Add the ice water and gently mix with your hands, tossing the flour into the liquid. Knead gradually, just until the dough comes together, adding more water 1 tablespoon (15 g) at a time, if needed.

At this point, I like to tip the dough onto the bench and bring it together with a dough scraper, lifting and folding it over itself a few times. I flatten it with the palms of my hands as I go.

Wrap the dough in clingfilm and chill in the freezer for at least 30 minutes, or overnight in the fridge.

On a lightly floured surface, roll the dough into a 1cm-thick rectangle. Brush off excess flour and fold in thirds, like a letter.

Turn the dough so the spine is on your left, then roll and fold once more. Wrap and chill in the freezer for 30 minutes.

Turn the dough again so the spine is on your left, then repeat the rolling, folding, and chilling process 2 more times, keeping the dough cold throughout. By the end, you will have completed 4 letter-folds in total.

After the final fold, divide the dough into 2 pieces and wrap in clingfilm. Refrigerate for at least 1 hour, and up to 5 days, before using. You can also freeze the dough at this stage.

Make the filling

Preheat the oven on grill mode to 270°C / fan 250°C.

Butter an 18cm cake tin and set aside.

Roll out the rough puff pastry onto a lightly flour surface. Line the prepared cake tin, docking the base with a fork. Chill in the freezer while preparing the filling.

In a bowl, whisk together the goat cheese, 130 g sugar, egg yolks, milk, salt, vanilla sugar, and cognac until smooth, then add the flour.

In a separate bowl, whip the egg whites with a pinch of salt. When moussy, add the 20 g sugar and whip to soft peaks. Gently fold them into the cheese mixture, see technique note above.

Bake

Pour the filling into the lined tin.

Bake in the pre-heated oven for 5 minutes, then lower the temperature to 250°C / fan 230°C and bake for 15 minutes.

Reduce the oven to 180°C / fan 160°C and bake for 40–60 minutes, until puffed.

Let cool completely on a rack before unmoulding – the cake will deflate slightly as it sets.

Serve in wedges, with loosely whipped cream and the topping of your choice. I love berries, or a slightly salty confiture de lait; a scoop of ice cream is never wrong either. Or eat plain, as a snacking cake.

Thanks for sharing this recipe Fanny and all its history. What an amazing cheesecake. Can't wait to give it a try. ❤

Quelle entrée en matière ! Un véritable reportage :) Merci pour les recettes, cela me donne envie de (enfin) tester cette délicieuse tradition. Une note sur le beurre salé dans la pâtisserie : en tant que normande je suis partisane du beurre doux et comme toi avant je n'arrive vraiment pas à l'utiliser en pâtisserie, mais peut-être qu'un jour je me tromperai dans le rayon et que cela se transformera en révélation ^^