Rhubarb toscakaka with vaniljsås

For when the garden is still sleeping, and the custard waits with you.

Welcome to The Bakers’ Cottage – a newsletter about recipes, stories, and the quiet rhythm of baking in the north. If you enjoy what I write and want to support my work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. It helps me spend more time developing recipes, writing, and keeping this space filled with good things.

Today’s post is for the in-between season – a rhubarb toscakaka baked golden under a layer of almond caramel, served with a pale, pourable custard. You’ll find the full recipe and notes below.

If your email cuts out, you can view it in full on the website or in the app.

By the time the first stalks start to show here, the rest of the world has already moved on. The season begins in early February – rhubarb, forced in candlelit barns, bundled in neat pink rows at markets, baked into galettes, churned into sorbet. Meanwhile, in northern Sweden, the garden is still under snow.

Living here means working at a different pace. It can be disorienting, watching the food seasons shift months ahead of your own. Especially when you’re trying to write from where you are – when what you have in your kitchen comes weeks or even months after it appears everywhere else. But I’ve found that there’s something grounding in it, too. You wait. There’s a kind of pirrigt anticipation in it – that quiet, fluttery longing that builds just before things begin.

Right now, it is very much spring. The snow on the ground melted weeks ago, during a brief stretch of warmth that came surprisingly early. But the air is cold again, even in the sun. It still snows, now and then – light flurries that don’t stay, but remind us that winter isn’t far behind.

So I made a cake for this in-between time. Something golden and just a little nostalgic, made with rhubarb from the freezer and a spoonful of vaniljsås. A cake for crossing over – from wool socks to rubber boots, from quiet cups of tea to long days with no set meal times.

Rhubarb toscakaka with vaniljsås

Toscakaka is a Swedish classic – a soft, buttery sponge baked under a layer of golden almond caramel. It’s often served plain, the topping cracking slightly as you cut into it. But I like it best with something sharp – either folded into the crumb or served alongside. Berries, stewed fruit, or here, rhubarb. It makes the whole thing feel like something you’d eat with a spoon, not a fork.

We don’t really know where the name comes from. Both Beatrice Ojakangas and Signe Johansen mention Puccini’s Tosca – a dramatic opera, wildly popular across Europe in the early 1900s – as a possible reference. I can’t help but think of Florentines, those thin, caramelised nut biscuits that feel close to the almond topping. Florence is in Tuscany. Toscana. Tosca?

Though it’s tempting to tie the topping to Florence, food writer Emiko Davies points out that Florentine cookies aren’t Florentine at all – likely French in origin, and created in honour of Catherine de Medici’s Tuscan roots. But maybe that’s the point. The name Tosca carries with it a swirl of imagined Italy – dramatic, baroque, just foreign enough to feel elegant. A name that sticks.

The caramelised almond crust itself has become a classic in Sweden. It started with cake, but you’ll now find toscabullar, toscakakor, toscamazariner – all topped with that same buttery, golden caramel.

And since this is a cake that wants custard, I made vaniljsås. The kind you pour in pale, pale yellow ribbons.

Notes on vaniljsås development

I developed my crème anglaise recipe during my time at Brasserie Chavot in London, where we served it with wonderfully light îles flottantes and a thick salted caramel. It was rich, yolk-thickened, and barely set.

But for this toscakaka, I wanted something closer to Swedish vaniljsås – a lighter mouthfeel and colour, and a slightly thicker pour.

I started by comparing formulas from four Swedish bakers, and threw in Jason Atherton’s English-style custard recipe too, along with my own crème anglaise for reference. I first analysed the ratios using baker’s percentages, treating the total liquid (milk + cream) as 100%, rather than flour as in traditional dough calculations.

I also looked at composition percentages, especially to assess the total sweetness and texture of each recipe.

For custards, I find that composition percentages are actually more relevant than baker’s percentages.

Baker’s percentages are great when you’re working from a fixed base – like flour in bread – and scaling everything else around it.

I still find them interesting for a quick overview of a recipe, just to get a feel for the ratios.

In custards, there isn’t a single dominant ingredient. You’re balancing yolks, sugar, and starch against the liquid.

For judging the final texture and sweetness, composition percentages – how much yolk, sugar, and starch there is per 100 g of custard – give me a much clearer picture.

The ratios

A base of milk only, a milk–cream blend, or cream only.

8–23% egg yolks.

Sweetness: 4.3–12.1% of the total weight (composition percentage). Three of the Swedish vaniljsås recipes are very lightly sweetened, with around 4–6 g sugar per 100 g of custard.

For reference, I like light compotes, coulis, gels, and custards at 10 g per 100 g (10% composition) – it’s a good starting point. For a more standard compote, I usually start at 20%, depending on the fruit.Starch: Two of the Swedish recipes use potato starch, the other two use cornstarch. The composition percentage for starch ranges from 1.8–2.5%, with the exception of Jason Atherton’s English-style custard, which uses only 1% – but with a much richer egg content, which also acts as a thickener.

Comparing the different formulas

Cecilia Lundin: lowest yolk and sugar content – milk-based, thickened with potato starch; whipped cream is folded in once cooled for a mousse-like finish.

Fredrik Nylén: 10% yolks, 100% cream base, highest potato starch content.

Camilla Hamid: 15% yolks, 1:1 milk and cream, high cornstarch content.

Mia Öhrn: milk-based, richer in yolks and sugar.

Jason Atherton: 23% yolks, 100% cream – the richest and sweetest of them all, a Bird’s style custard with little starch.

My crème anglaise: 15% yolks, 65% milk / 35% cream, no starch. Lightly sweetened, at 8.6% of the total weight.

My vaniljsås 1.0

I chose each percentage with the final texture in mind. I wanted enough yolk to give a slight flavour and richness, but not so much that it tipped into anglaise territory. The sugar sits at 10% – though you could easily go a little lower or higher, depending on your taste.

For starch, I settled on potato starch, partly out of tradition – and although it worked well, I don’t think I’ve quite found my perfect Swedish-style vaniljsås yet.

To-do: a small mixture design experiment, adjusting three main variables:

Starch: comparing cornflour and potato starch, and playing with different percentages.

Milk to cream ratio: seeing how a higher or lower fat content shifts the mouthfeel.

Egg yolk percentage: testing richer and lighter custards.

In the meantime, here’s the formula I landed on:

Liquid base

90% whole milk

10% cream

Thickening

8% egg yolks (bakers’ percentage)

2% potato starch (composition percentage)

Sweetening

10% sugar (composition percentage)

Vanilla

I often use two to three vanilla pods per litre of liquid – split and scraped, then infused in the milk-cream mixture

Salt

A pinch of salt, of course. Always.

Potato starch

Potato starch deserves its own story. It’s more than just a thickener – it’s a deep-rooted part of the Swedish food culture. Known as potatismjöl, it was first produced in 1746, when agronomist Eva Ekeblad discovered a method to extract starch from potatoes, transforming them into flour and alcohol. It soon became widely available and was used in everything from vaniljsås to fruit soups, berry puddings, and sponge cakes. Before industrial cornstarch became common in home kitchens, potatismjöl was the everyday thickener. It’s a texture and tradition I want to honour here.

Functionally, potato starch and cornstarch behave similarly. Both thicken when the starch molecules swell and gelatinise in the presence of heat and liquid. Potato starch can be used as a 1:1 substitute for cornstarch by weight, and it performs in much the same way.

In lighter custards, I find that potato starch – which has a lower gelatinisation temperature – produces a silkier texture. Cornstarch must be fully cooked to avoid a residual starchiness.

In recipes where a firmer, sliceable texture is needed – like pie fillings – you might prefer to use cornstarch, or increase the amount of potato starch to achieve the same set. Cornstarch contains slightly more amylose than potato starch – about 25% compared to 20% – and amylose is the molecule responsible for gel strength.

For more on the cultural history of potatoes in Sweden, I recommend this excellent piece by Year on the Field: From farm to fork – about the history of potatoes in Sweden.

Notes on sponge development

I needed the right sponge – something that could carry the rhubarb and the crisp almond caramel without sinking. A moist crumb, quite sweet.

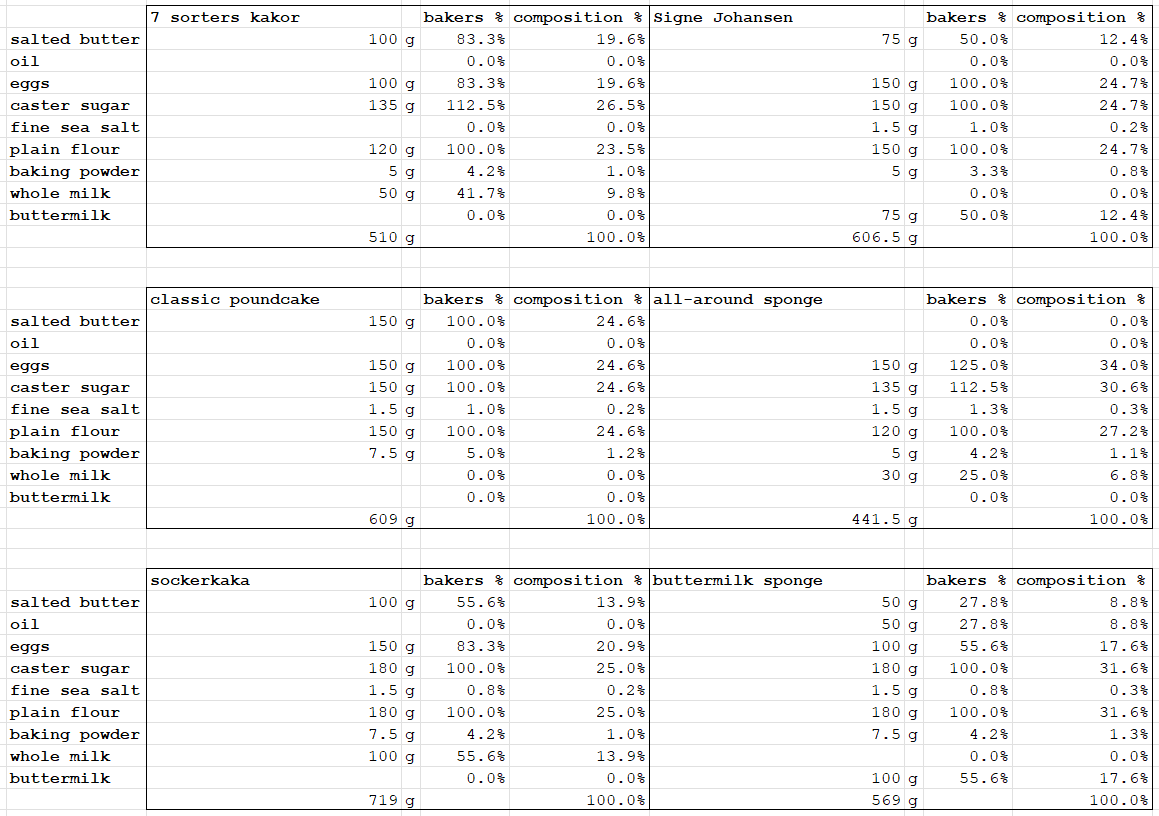

I compared a handful of classic toscakaka bases, a pound cake–style formula, and three of my own reference sponges: my all-around sponge – a more stable genoise – my everyday sockerkaka [sugar cake], and my favourite buttermilk sponge.

(Although I say buttermilk, I actually use filmjölk – a Nordic fermented milk product that can easily be swapped for buttermilk.)

I wasn’t looking for the airiest crumb – just something tender and sturdy enough to hold it all together.

In the end, I built my formula from scratch. I wanted the tang and softness that buttermilk brings, not too much butter, and a batter sweet enough to balance the rhubarb.

Toscakaka is traditionally a thinner sponge before it gets topped. Most recipes I’ve come across yield around 500–600 g of batter, baked in a 23–24 cm cake tin – which would mean the batter is only about 1.7–2 cm thick before baking.

I wanted mine a little higher, but still fitting into a 20 cm tin, filled to about 2.5–3 cm. Now, I am not sure this is remotely interesting to anyone but me – but I’ll add my process, just in case.

Volume cylinder = π x r² x h

where:

r=10cm (half of 20 cm)

h=2.5–3cm

For 2.5 cm height: π × 10² × 2.5 ≈ 785 cm3

For 3 cm height: 𝜋 × 10² x 3 ≈ 942 cm3

So for my desired thickness, the volume is 785–942 cm³.

___

Estimated batter density = 0.7g/cm3 (water density = 1g/cm3)

Note: A very light sponge has a density close to 0.5g/cm3 and a pound cake is closer to 0.8–0.9g/cm3.

So to fill the tin:

At 2.5cm: 785 × 0.7 ≈ 550 g

At 3cm: 942 × 0.7 ≈ 660 g

___

Adding the rhubarb:

150 g rhubarb added into the batter

Rhubarb density ≈ 1 g/cm³

Now we have a mix of batter (0.7 g/cm³) + rhubarb (1 g/cm³).

The overall mixture density increases slightly.

Approximate new density ≈ 0.75 g/cm3

___

At new density 0.75 g/cm³:

785 × 0.75 = 589 g

942 × 0.75 = 706.5 g

I need about 590–705 g total of batter, including the rhubarb.

___

The final weight:

500 g sponge batter

+ 150 g rhubarb

Total ≈ 650 g The sponge

I started with two eggs – it felt like three might yield too much batter – and built the rest of the formula around them, trying to stay close to the ratios I have in my sockerkaka.

This is the recipe I used:

The almond topping

For the almond caramel, I used a recipe I had scribbled down in my notebook – just adjusting the sugar slightly, from 150 g to 100 g, and added a pinch of salt.

Rhubarb toscakaka

MAKES one 20cm cake

For the sponge

65 g salted butter, melted and cooled slightly

100 g eggs (about 2 large)

150 g caster sugar

1 tsp vanilla sugar or ½ tsp vanilla extract

140 g plain flour

1 heaped tsp baking powder (about 6 g)

A pinch of fine sea salt

65 g filmjölk or buttermilk

150 g rhubarb (fresh or frozen), cut into small pieces

For the almond topping

50 g salted butter

100 g caster sugar

1 tbsp plain flour

2 tbsp whole milk

A pinch of fine sea salt

150 g flaked almonds

Make the sponge cake

Preheat the oven to 175°C / fan 155°C. Grease and line a 20 cm round springform tin.

In a large bowl, whisk the eggs, sugar, and vanilla until light and slightly thickened.

In a separate bowl, sift together the flour, baking powder, and salt.

Stir the melted butter and filmjölk into the egg mixture.

Gently fold in the flour mixture, followed by the rhubarb.

Pour the batter into the prepared tin and smooth the surface.

Bake in the lower part of the oven for about 30–40 minutes – the sponge should feel set and start to colour but still pale.

Prepare the almond topping

When the cake is almost ready, melt the butter. Add the sugar, milk, and flour. Let it just come to a simmer, then remove from the heat.

Stir in the flaked almonds and stir well.

To finish the cake

Remove the sponge from the oven and gently spread the almond topping over the surface.

Return the cake to the middle of the oven and bake for another 15–20 minutes, until the topping is golden and bubbling.

Let the cake cool in the tin for about 30 minutes before transferring to a wire rack.

Serve in wedges with a generous spoonful of cold vaniljsås poured over the top.

Vaniljsås

MAKES 600 mL custard

450 g whole milk

50 g whipping cream

40 g egg yolks (about 2–3 large yolks)

62.5 g caster sugar

12.5 g potato starch

1 vanilla pod, split and scraped

A pinch of fine sea salt

In a saucepan, combine the milk, cream, and vanilla pod. Bring just to a simmer, then remove from the heat and let infuse for 10–15 minutes.

In a separate bowl, whisk together the egg yolks, sugar, potato starch, and salt.

Remove the vanilla pods from the milk mixture and bring it back to a simmer.

Gradually whisk the hot milk into the yolk mixture, then return everything to the pan.

Cook over low heat, stirring constantly, until the custard thickens slightly and just starts to simmer.

Strain into a clean bowl, clingfilm to the touch and chill in the fridge until needed – for at least 2 hours and up to 3 days.

Wow Fanny, thanks so much for this post and for sharing the details of your recipe development. It is so helpful and enlightening.

The cake looks amazing and I can't wait to give the custard a try!

Wow I have learned so much from this post! I have been attempting to play with my own cake recipes and failing miserably. This broke the process and approach down to every facet (texture, crumb, sweetness, volume) so beautifully. My husband is a math teacher, and I will be having him help me work through my own formulas for cake batter ❤️ thank you!