Custard-filled solbullar and the way we Easter

Birch branches, vintage ceramic chicks, yellow ribbons, and what I cook this time of the year.

Welcome to The Bakers’ Cottage – a newsletter about recipes, stories, and the quiet rhythm of baking in the north. If you’re new here, thank you for joining. And if you’re already a subscriber – I’m so glad to have you back.

If you enjoy these posts and want to support my work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. It helps me continue writing, testing recipes, and sharing them here.

Today’s post is a glimpse of Easter, the way we celebrate it here in our home – with birch twigs in a jar, vintage chicks from the loppis, and a table that leans more toward the sea than the lamb. There are forest walks, fire-cooked waffles, and soft buns filled with vanilla custard – fried until golden, then dusted with sugar.

You’ll find the recipe for solbullar below, along with a few stories from our kitchen and the dishes we return to each spring.

This is a rather long post, so if your email cuts out, you can view it in full on the website or in the app.

Easter is late this year. I never quite know which I prefer – the ones that arrive in March, when winter still lingers and the snow lies deep, or those that wait for April light and the first shy buds on the birch trees.

The early ones feel hushed, wrapped in white and stillness. The late ones are softer somehow – full of light, yellow bows, and the quiet unfolding of the season.

This is when I crave brightness on the plate and warmth in my hands. Cured fish and roe, herbs and citrus, waffles cooked over fire, and solbullar – sun buns, baked when the light comes back.

In Sweden, Easter isn’t loud. It doesn’t shout the way Christmas does. There are no months of build-up, no long lists. But still, it comes. With a bouquet of decorated birch twigs. With hand-drawn cards from children dressed as påskkärringar [Easter witches] in kerchiefs and aprons, going door to door with baskets and freckles penciled on their bright-red, blushed cheeks. With eggs, of course: blown-out and painted, boiled and devilled, or filled with sweets. Not hidden in the garden, usually – there’s still too much snow – but in a cardboard egg, large and hollow, tucked with foil-wrapped chocolates and small surprises.

At the table, it looks a little like Christmas, or midsummer: pickled herring, gravlax, Jansson’s temptation, smoked salmon, mustard glazed ham, roast lamb, and plenty of hard-boiled eggs. Bowls of gubbröra, platters of crispbread, and often a bottle of påskmust – the sweet, dark soda that appears only twice a year: once at Christmas, once at Easter, in near-identical bottles.

Our Easter table is a little different.

We keep the birch twigs, but not the feathers. Traditionally, Swedes tie them into their påskris – a symbol of life returning – but I try to take a more sustainable approach. Instead, we decorate with yellow ribbons and a small flock of vintage ceramic chicks I found at the loppis [thrift store] last year, each one carefully unwrapped from its paper nest. There are painted eggs from when Sienna was little, and flowers cut from egg cartons, strung on white cotton twill tape. Everything lives in an old metal chocolate tin that we open the week before Easter.

And there’s no lamb in sight. These are the days when I want my fridge to look like a fishmonger’s window display – and an herb garden, all at once.

There might be queen scallops, quickly seared and dressed with brown butter, coriander, chili and ginger. Cured salmon – gravlax – always served with tunnbröd, soft salted butter, boiled potatoes and a generous spoonful of hovmästarsås. ½ filled with shrimp and heavy on the mint. Moules à la crème with thin, crisp shoestring fries. Buckwheat blini with Swedish caviar and smetana, lemon wedges and plenty of chives.

A tomato galette with brie and wild garlic. Lightly toasted sandwich bread topped with crème fraîche and roe – löjrom, stenbitsrom, or forellrom. A warm potato salad with shallots, Dijon, tarragon and capers. A few prinskorvar. A small plate of sill – always Brantevik, because it’s the best. Pickled herring with shallots, dill, lemon zest, black pepper, white pepper, allspice, distilled vinegar and a splash of akvavit.

There’s burrata with melon and coppa. A simple ham and cheese macka [open sandwich], eaten in the sun with pea shoots tumbling out the sides. And always, on Easter Sunday – smörgåstårta. A towering, savoury sandwich-cake, layered with prawns and eggs and cucumber ribbons.

Some years, we grill smashed burgers by the fire pit. Or sit around the table peeling smoked shrimp, dipping them into aioli and scooping up the rest with torn baguette. There’s matjesillsallad – a dish made with pickled soused herring, sour cream, crème fraîche, chives, shallots, boiled eggs, and sometimes a few cubes of cooked potato. It’s salty, creamy, bright.

When the weather allows, we take it outside.

Solbullar filled with more vanilla custard than bun, packed into a tin and brought along for forest walks. Saffron bullar, pan-fried on our stormkök [camping stove] deep in the woods – crisp on the outside, soft in the middle. Waffles cooked over fire in our old cast-iron våffeljärn, topped with jam and cream, or better yet, with crème fraîche, avocado, löjrom, chili and coriander – best eaten with cold fingers and flushed cheeks.

A classic toast Skagen, made with hand-whipped mayonnaise and freshly cured stenbitsrom, plump and pale dusky rose. Pizza dough cooked in a hot pan, then folded and filled with spicy spianata calabrese and crunchy salad. Or katmer for breakfast – flaky flatbread with bacon, avocado, fried eggs, and a bowl of fruit salad on the side.

Sometimes pissaladière, sometimes nothing at all – just a cup of coffee and the smell of spring coming through the windows.

And then there’s dessert. Anything rhubarb.

A mousse cake with raspberries and yoghurt. Or a tiramisu, the sponge soaked in rhubarb juice and layered with mascarpone cream. Some years I bake a simple sockerkaka, then top it with whipped mascarpone and gently poached stalks – simmered in raspberry syrup until just soft and blushing. We serve it with a pouring of vaniljsås.

I also love something tart alongside something soft – like a scoop of passionfruit sorbet from the shop, with lightly whipped cream and crumbled meringues.

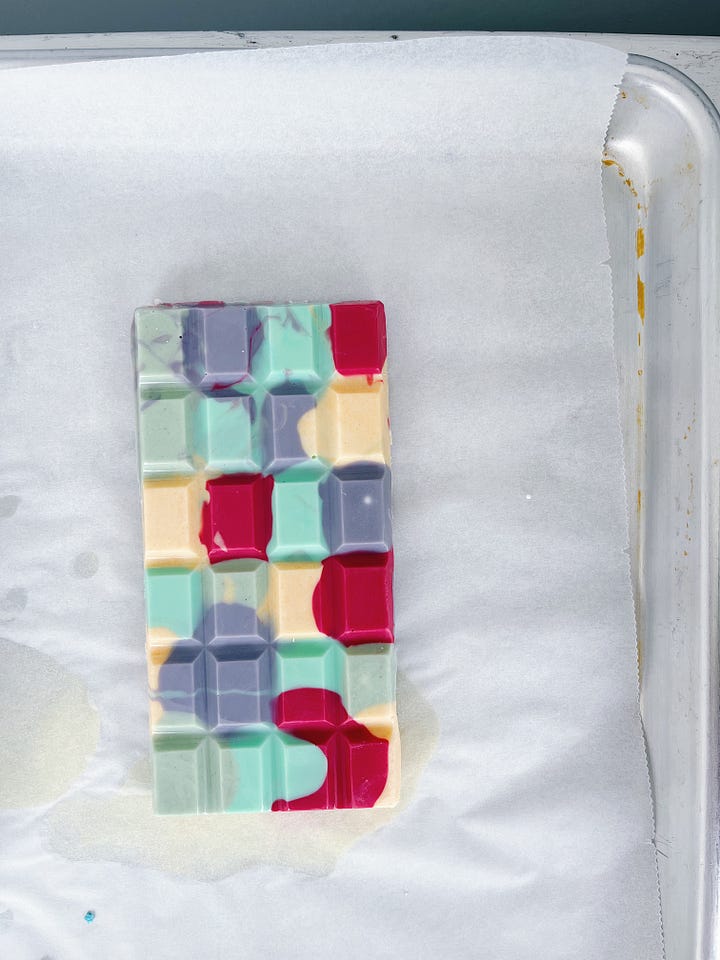

Sometimes we make our own chocolate eggs, filled with ganache or friture – moulded fish and seashells. Other times, I’ll order a box of pralines from Chocolatte in Helsingborg – my favourites, chosen one by one after the table is cleared and the coffee is poured.

And then, if we’re lucky, the first strawberries. Not many – just a handful, sweet and still a little cool. We serve them with vaniljkräm and a few kolakakor, their edges golden and chewy. Or I’ll grate some frozen ones from last summer over cold vanilla yoghurt – a soft snow that melts as you eat, tart and full of sun.

Solbullar, custard-filled sun buns

We bake these solbullar sometime after the spring equinox – to celebrate the return of the sun. Soft, golden buns scented with cardamom and filled with vaniljkräm. Not too sweet, just enough. Once they’ve cooled slightly, I brush them with melted butter and roll them in sugar.

Sometimes, though, I wait. We pack them into a tin and take them with us instead – out into the woods, where the snow is melting and the sun sits a little higher in the sky. There, on the stormkök, I fry them in salted butter until their edges turn crisp and golden. A final dusting of sugar, and they’re ready – a little too hot to eat with bare fingers.

Notes

On cardamom

I like to use freshly ground cardamom seeds. In Sweden, they’re easy to come across, but cracking open green cardamom pods works just as well. Inside, you’ll find tiny black seeds – crush them by hand with a mortar and pestle. If you’re in a hurry, you can grind a larger batch and keep it in a small airtight jar for later use, although nothing beats the freshly-ground flavour.

On fresh yeast and salted butter

I work exclusively with fresh yeast and salted butter.

If using instant dry yeast instead, use about one-third the amount:

15 g fresh yeast = 5 g instant yeast (roughly 1½ tsp).

If you’re using unsalted butter, you might want to add a pinch more salt to the recipe – though you may find it to your liking as it is.

On piping custard

If your custard feels too firm after chilling, give it a good stir to loosen it before piping. The filling should be added just before baking – if piped too early, the buns may deflate. Use the nozzle to gently pierce through the top of each bun, then pipe until the bun swell slightly.

Piping the custard takes a bit of practice. Sometimes it slides right back out, no matter how gently I press. Sienna loves to help – which means our buns are often a little lopsided. But those are the ones that end up with the most custard, and we always fight over who gets to eat them.

On frying over fire

Frying buns on the stormkök or over an open fire is one of my favourite parts of Easter. Use a camping stove pan or a cast-iron skillet, and warm it above the flames. Melt the butter, then add the buns and turn them gently to coat. Let them crisp slowly on the outside and warm through in the middle.